Safety experts and activists are asking numerous questions concerning the fire which devastated the U.S. East Coast’s largest and oldest refinery, Kallanish Energy understands.

One big question is how did a piece of piping installed in the early 1970s go without once being checked before leading to the fire at the Philadelphia Energy Solutions (PES) refinery in June?

Another important question is, are more disasters waiting to happen in an industry reliant on decades-old equipment?

Record-setting production, using decades-old infrastructure

In 2018, U.S. refineries processed nearly 17 million barrels per day (Mmbpd) of crude oil — the most in the country’s history, Reuters reported.

But many refineries utilize decades-old infrastructure, risking outages that could cost the industry billions of dollars. The PES refinery is one of nearly 30 in the U.S. with sections of the complex more than 100 years old.

A Reuters review of over 100 operating U.S. refineries that process more than 10,000 barrels per day of crude showed they are on average 80 years old.

Equipment installed in the 1970s

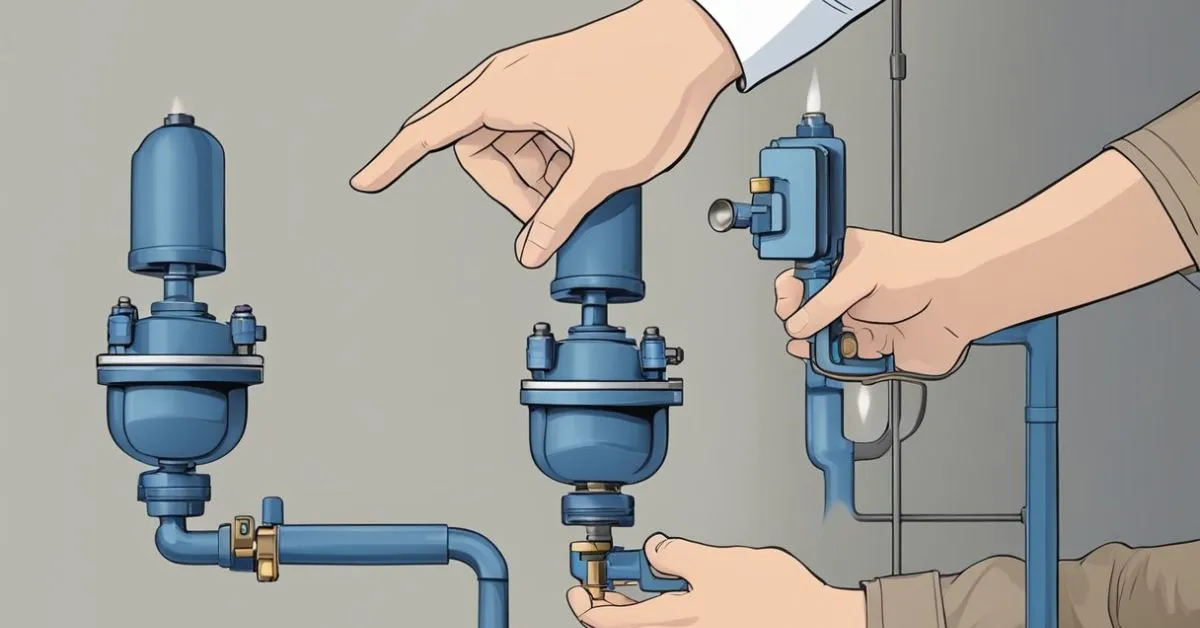

Refineries frequently update their systems and replace old parts, but the PES fire stemmed from equipment installed in the 1970s that had been allowed to run to failure, according to U.S. Chemical Safety Board (CSB) reports, Reuters reported.

The suspected cause of the PES explosion has raised fears about future incidents because of the leeway given to refiners for inspecting parts, and because some older equipment is exempt from more stringent standards for newly installed parts, Reuters reported.

“A lot of these refineries around the U.S. are quite old now,” former CSB managing director Daniel Horowitz, who left the agency last year, told Reuters.

“That doesn’t mean that every single piece of equipment dates back to the founding, but they are old and eventually all sorts of components can fail.”

Corroded piping

The June 21 Philadelphia blaze was linked to corroded piping that had not been checked since it was installed in 1973, according to the CSB’s initial findings. The fire is still under investigation by the CSB and other public agencies.

It caused a fuel leak and explosions that sent toxic hydrofluoric acid (HF) into the air and hurled debris the size of a tractor-trailer across the Schuylkill River, the CSB’s report said.

Shortly after the fire, PES filed for bankruptcy protection.

Exemptions given

The failed equipment contained metal components or designs no longer up to industry standards, but their use did not necessarily violate regulations. Regulators offer exemptions for older components, and do not require all pieces of plant machinery to be checked.

“That’s a huge problem in this sector, that a lot of codes allow grandfathered equipment to be used even if later standards would have prohibited it,” said Horowitz.

The CSB report spurred a letter from top law enforcement official in 13 states, including Pennsylvania, to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), arguing against a proposed rollback of regulations aimed at preventing accidents involving chemicals such as HF.

Regulators overseeing U.S. oil refinery safety, primarily the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the EPA, and code-setting industry groups allow some refinery components to keep being used even if they don’t meet newer standards.

The EPA and OSHA were unavailable for comment.